Title

Title

Robert Mathieson (the First Settler of Manhattan Beach) and the Spirit Lake Massacre

July 1856 - March 1857

Title

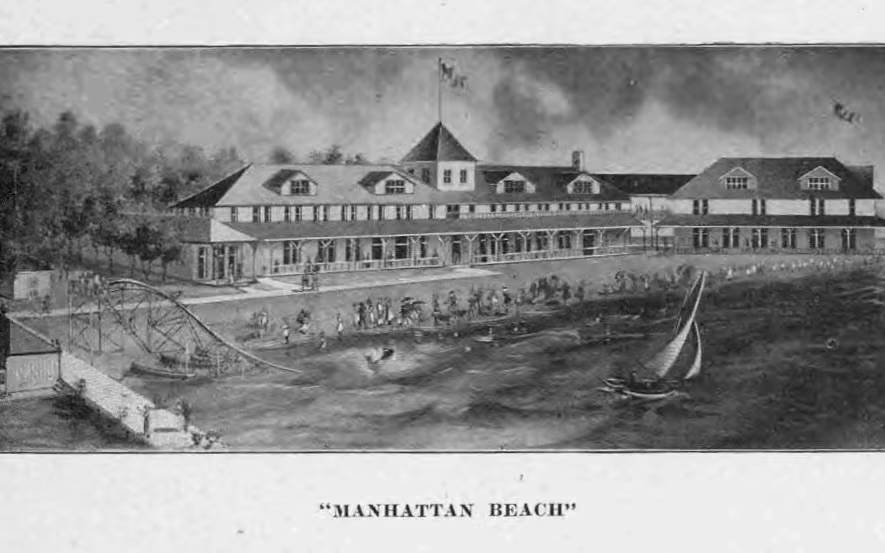

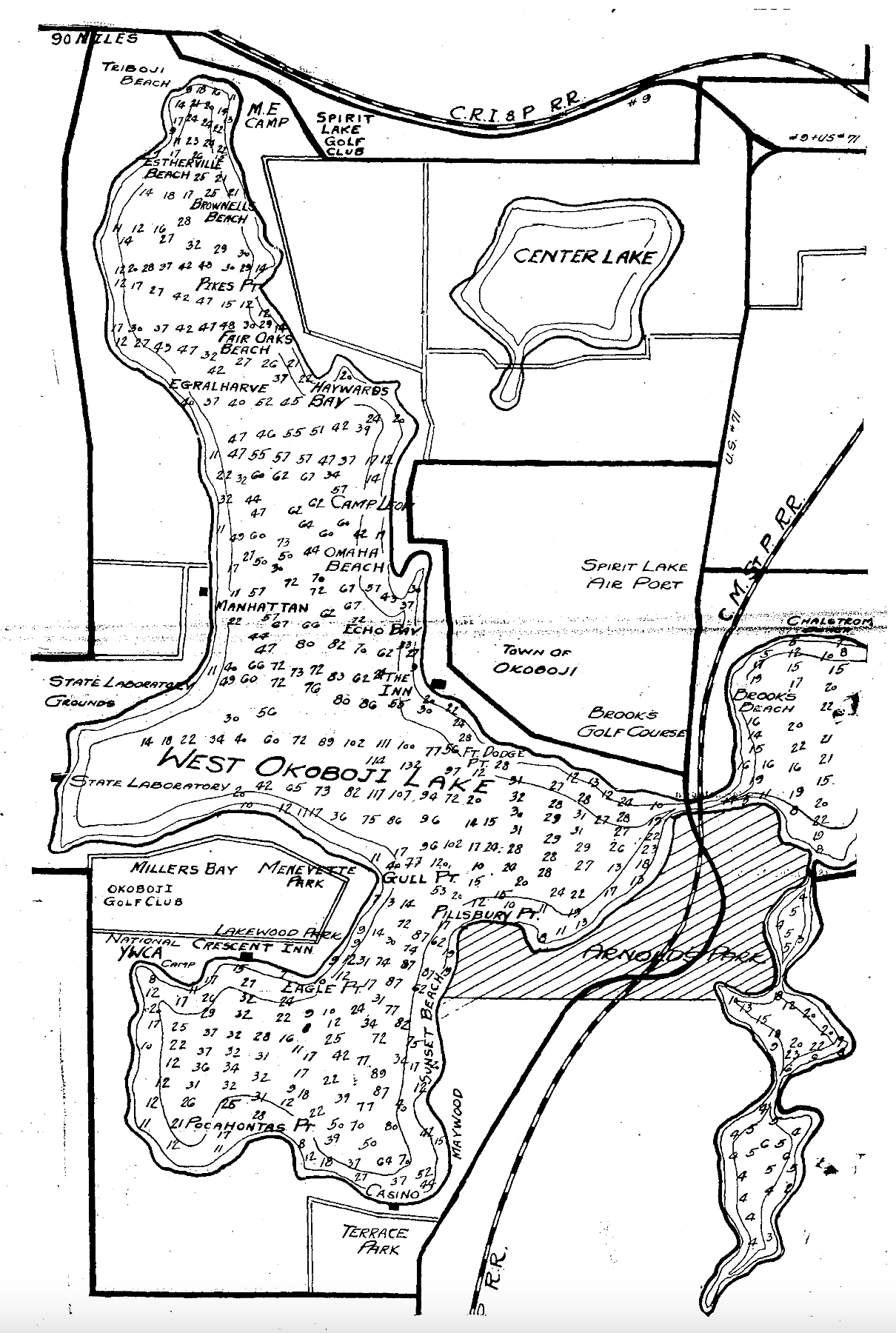

David B. Lyons and the Manhattan Beach Company

January 11, 1892 - March 30, 1899

Title

Joseph I. Myerly Revitalizes the Manhattan Hotel

October 15, 1900 - August 24, 1911

Title

Owners of the Manhattan Beach Hotel

August 24, 1911 - December 27, 1932

Title

Hobart A. Ross Rebuilds Manhattan Beach

December 27, 1932 - September 1, 1949

Title

Nic and Josephine Kamp Bring Family Fun to Manhattan

September 1, 1949 - March 15, 1957

Title

Chick and Lucile Evans Expand Manhattan Beach Resort

March 15, 1957 - May 5, 1975

Title

Dick and Linda Fedora Sustain Manhattan Beach Resort

May 5, 1975 - July 14, 1984

Title

Chuck and Denise Long Preserve Manhattan Beach Resort

July 14, 1984 - Present

Title

Okoboji Flood 2024

June 17, 2024 - July 20, 2024

Title

Title